- A Short History of Vienna

- A Short History of the Jews in Vienna

- Feng Shan Ho

- A Short History of Shanghai

- A Short History of the Jews in China

A Short History of Vienna

Romans to the Hapsburgs

Movie Clips

In the first century CE, the Romans established a military camp at what was previously a Celtic trading post and called it Vindobona. Emperor Marcus Aurelius died there in 180 CE during a military campaign. The Romans were driven out in the 5th century and the site was inhabited by a succession of invading groups culminating with the Magyars.

The Magyars were defeated by Emperor Otto I, and what by then was known as Wenia became the centre of the Babenberg dynasty around 1146. In 1241, Vienna marked the westernmost incursion of the Mongol invasion of Europe. Only the death of the Mongol Khan saved Vienna – and Europe – from being overrun by Mongol armies. Vienna was subsequently inherited by the Habsburgs and the city grew in both size and prestige. Vienna University, one of the oldest universities in Europe was established in 1365.

In 1556, after the Habsburgs had gained Bohemia and Hungary, Vienna became the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The city was besieged by Ottoman Turk forces several times, until the Ottomans were decisively driven back in the Battle of Vienna in 1685. In subsequent decades, the city prospered and saw major building projects, many by famous architects.

19th Century

Vienna was seized twice by Napoleon, in 1805 and 1809, before he was finally defeated at Leipzig and the Congress of Vienna (1814-15) restored the balance of power in Europe. The revolutionary wave that swept Europe in 1848 also saw an uprising in Vienna that was quashed by Emperor Ferdinand I’s army. Ferdinand’s nephew Franz Joseph acceded to the throne shortly thereafter and presided over a period of growth and the flowering of arts and culture, especially music in the works of Gustav Mahler, Johann Strauss, Franz Schubert and Johannes Brahms.

World War I to Anschluss

The assassination of the heir to the throne Archduke Franz Ferdinand sparked WW1 which saw Austro-Hungary, Germany and the Ottoman Empire defeated by the Entente Powers (mainly France, Russia and the UK) in 1918. This marked the end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the beginning of the Republik Osterreich, which was characterized by economic difficulty and political polarization. In February 1934, Vienna was the site of many of the skirmishes between socialist and conservative-fascist forces that constituted the Austrian Civil War, after which time parliament was controlled by a single, authoritarian party. The state of Austria ceased to exist in March 1938 when it was invaded and annexed by Nazi Germany, a move most Austrians welcomed.

World War II and Post-war

In the early years of the war, Vienna was out of range of Allied bombers operating from England; this changed in 1943, when the city was attacked by bombers based in Italy, and suffered heavy destruction. Conquest of the city by Soviet troops in April 1945 also caused significant damage. After the war, Vienna was divided into five zones occupied respectively by the USSR, the US, the UK and France, with the fourth patrolled by all four. A provisional municipal council was put in place until 1955, when the country regained its sovereignty.

Postwar Vienna saw an economic boom, as a result of Marshall Plan aid. In the 1970s, the city became the third official seat of the United Nations.

A Short History of the Jews in Vienna

The Middle Ages: Persecution and Persistence

Movie Clips

There is evidence of a Jewish presence in Vienna as early as 1194; Jewish community institutions like hospitals, synagogues and slaughterhouses have existed since the 14th century. The area that is modern-day Judenplatz was a centre of Jewish religious and cultural life until 1420 when Jews were expelled from the city, their property confiscated, and one of the largest synagogues in Europe destroyed. Jews were allowed to return in 1451, with protection from the Hapsburg emperors. 1624 saw a wave of Jewish immigrants, fleeing pogroms in the Ukraine, to Vienna. They were granted their own section of the city in what became known as Leopoldstadt. This ghetto, including its two synagogues, was destroyed, and the Jews expelled again in 1669 by Leopold I. Negative economic repercussions of this expulsion caused the emperor to invite wealthier Jews to return. Among them were Samson Wertheimer and Samuel Oppenheimer, known as “Court Jews” who became influential advisors to the emperor in dealing with Turkish invasions.

Empress Maria Teresa, who reigned 1745-65, was fiercely anti-Semitic and passed many discriminatory laws. However, her son Emperor Joseph II issued an Edict of Tolerance in 1782, according Jews some of the same rights as Gentiles, including basic religious freedom. The Edict eliminated some previous restrictions, such as the requirement that Jews wear yellow circles or stars or pay additional taxes. It allowed Jewish children to attend schools and adults to become merchants, open factories, and learn trades, though they were still not allowed to become master craftsmen or to own property. Also, immigration of new Jews into Austria was severely restricted. Still, some families, in the trades and in banking, began to acquire significant wealth and political influence.

19th Century: Cultural Blossoming

Many Jewish intellectuals joined revolutionary forces in 1848, seeing it as an opportunity to further the cause of emancipating their community. Jews in Austro-Hungary finally gained full citizen rights in 1867. By this time, Vienna had the largest Jewish population in the empire, and attracted many Jewish immigrants. In the latter half of the 19th and the early 20th centuries, Jewish culture bloomed and Jewish musicians, artists and intellectuals, like Gustav Mahler, Max Reinhardt, Franz Kafka and Sigmund Freud, contributed much to Viennese culture as a whole. Jewish merchants, businessmen, and entrepreneurs played a significant role in growing the city’s prosperity.

Many Jewish intellectuals joined revolutionary forces in 1848, seeing it as an opportunity to further the cause of emancipating their community. Jews in Austro-Hungary finally gained full citizen rights in 1867. By this time, Vienna had the largest Jewish population in the empire, and attracted many Jewish immigrants. In the latter half of the 19th and the early 20th centuries, Jewish culture bloomed and Jewish musicians, artists and intellectuals, like Gustav Mahler, Max Reinhardt, Franz Kafka and Sigmund Freud, contributed much to Viennese culture as a whole. Jewish merchants, businessmen, and entrepreneurs played a significant role in growing the city’s prosperity.

World War I: Patriotism and Refuge

During WW1, more than 50,000 Jewish refugees fleeing the Russian advance into eastern regions of the empire flooded into Vienna, most arriving at the Leopoldstadt train station. Nearly half of these refugees stayed in Vienna, and relations between Jewish and Christian communities became more strained. The Jewish community itself was divided between Orthodox Jews, often newer arrivals, who wished to live in line with traditional beliefs, and those who had lived in Vienna a long time and were largely assimilated into Christian society. They fully participated in German/Austrian cultural life, including all the stereotypes: ski holidays in the Alps, eating Black Forest cake at Viennese sidewalk cafes, drinking tankards of beer and dressing in traditional garb (suspenders, lederhosen and Tyrolean hats for the boys, dirndl skirts, starched blouses and braids pinned up in circles for the girls) to celebrate at festivals. Many Jews also fought for Austro-Hungary in the war.

During WW1, more than 50,000 Jewish refugees fleeing the Russian advance into eastern regions of the empire flooded into Vienna, most arriving at the Leopoldstadt train station. Nearly half of these refugees stayed in Vienna, and relations between Jewish and Christian communities became more strained. The Jewish community itself was divided between Orthodox Jews, often newer arrivals, who wished to live in line with traditional beliefs, and those who had lived in Vienna a long time and were largely assimilated into Christian society. They fully participated in German/Austrian cultural life, including all the stereotypes: ski holidays in the Alps, eating Black Forest cake at Viennese sidewalk cafes, drinking tankards of beer and dressing in traditional garb (suspenders, lederhosen and Tyrolean hats for the boys, dirndl skirts, starched blouses and braids pinned up in circles for the girls) to celebrate at festivals. Many Jews also fought for Austro-Hungary in the war.

Between the Wars: The Holocaust Begins

Anti-Semitism became more pronounced after the war, as attacks on Jews were encouraged by conservative political parties and Nazi organizations. Hitler rose to power in neighbouring Germany in 1933, and proceeded to make Germany judenrein (cleansed of Jews) by systematically curtailing their rights and freedoms until life was so difficult that they would be forced to leave the country. By 1938, one in four (150,000) German Jews had indeed fled.

Anti-Semitism became more pronounced after the war, as attacks on Jews were encouraged by conservative political parties and Nazi organizations. Hitler rose to power in neighbouring Germany in 1933, and proceeded to make Germany judenrein (cleansed of Jews) by systematically curtailing their rights and freedoms until life was so difficult that they would be forced to leave the country. By 1938, one in four (150,000) German Jews had indeed fled.

In Vienna, Jewish families continued to run their businesses (dry goods stores, banks, law offices, etc.) despite the climate of fear, telling themselves that in Austria, at least, reason would prevail. Their hopes were dashed on March 11, 1938 when German announced the Anschluss (annexation) and Hitler’s forces marched triumphantly into Vienna.

In the first week, Jews were fired from their jobs in libraries, theatres and community centres. Next were all Jewish state officials, judges and lawyers. Austrian lawyers in all courts were required to wear swastikas. Cases involving Jews were no longer brought to trial; they were automatically convicted for being Jews. In subsequent weeks Jews were fired from teaching and from markets. Kosher slaughter was forbidden. Jews found they were no longer welcome in the houses of non-Jewish friends. They were barred from theatres, restaurants and many shops.

Jews were accosted, jeered at and assaulted in the streets. In humiliating demonstrations, they were forced to scrub the pavement with toothbrushes, dragged to parks to get down on all fours and eat grass until they vomited, made to perform inane gymnastic tricks for the entertainment of jeering onlookers. Jewish cemeteries were desecrated. Newspapers printed ugly caricatures meant to ridicule.

Jews were accosted, jeered at and assaulted in the streets. In humiliating demonstrations, they were forced to scrub the pavement with toothbrushes, dragged to parks to get down on all fours and eat grass until they vomited, made to perform inane gymnastic tricks for the entertainment of jeering onlookers. Jewish cemeteries were desecrated. Newspapers printed ugly caricatures meant to ridicule.

All Jewish citizens were ordered to present themselves at a nearby government office with a detailed list of all possessions: bank accounts, property, businesses, gold, jewellery, and art. Jews who subsequently tried to draw funds from their accounts found them frozen. The Gestapo began systematically visiting all those Jewish homes and businesses where they forced residents to sign over ownership on threat of violence, leaving Jews with nothing and nowhere to turn.

World War II: “The Final Solution”

By the end of 1941 more than half of Austria’s Jews had fled the country, leaving all their property behind. After the Wannsee Conference in January 1942, at which the Nazis resolved to murder the entire Jewish population of Europe, more than 65,000 Austrian Jews were deported to concentration camps. Only 2000 survived. Before 1938, Vienna’s Jewish population was approximately 180,000; by 1946, only 25,000 remained, many of whom emigrated in the following years.

By the end of 1941 more than half of Austria’s Jews had fled the country, leaving all their property behind. After the Wannsee Conference in January 1942, at which the Nazis resolved to murder the entire Jewish population of Europe, more than 65,000 Austrian Jews were deported to concentration camps. Only 2000 survived. Before 1938, Vienna’s Jewish population was approximately 180,000; by 1946, only 25,000 remained, many of whom emigrated in the following years.

Post-War: Remembering

In the 1970s, Vienna became an important transit point for Jews allowed for the first time to leave the Soviet Union. Most continued on to Israel or the US, but some stayed. A 2001 census recorded approximately 7000 Jews living in Vienna, although some accounts put that number as high as 15,000. Anti-Semitism has persisted in Austria in the decades since WWII; a number of programs and institutions established by Viennese Jews in more recent years – for example, the Judenplatz Holocaust Memorial Museum which opened in 2000 – aim to educate Austrian society, and the world, about the role Austria played in the Holocaust.

In the 1970s, Vienna became an important transit point for Jews allowed for the first time to leave the Soviet Union. Most continued on to Israel or the US, but some stayed. A 2001 census recorded approximately 7000 Jews living in Vienna, although some accounts put that number as high as 15,000. Anti-Semitism has persisted in Austria in the decades since WWII; a number of programs and institutions established by Viennese Jews in more recent years – for example, the Judenplatz Holocaust Memorial Museum which opened in 2000 – aim to educate Austrian society, and the world, about the role Austria played in the Holocaust.

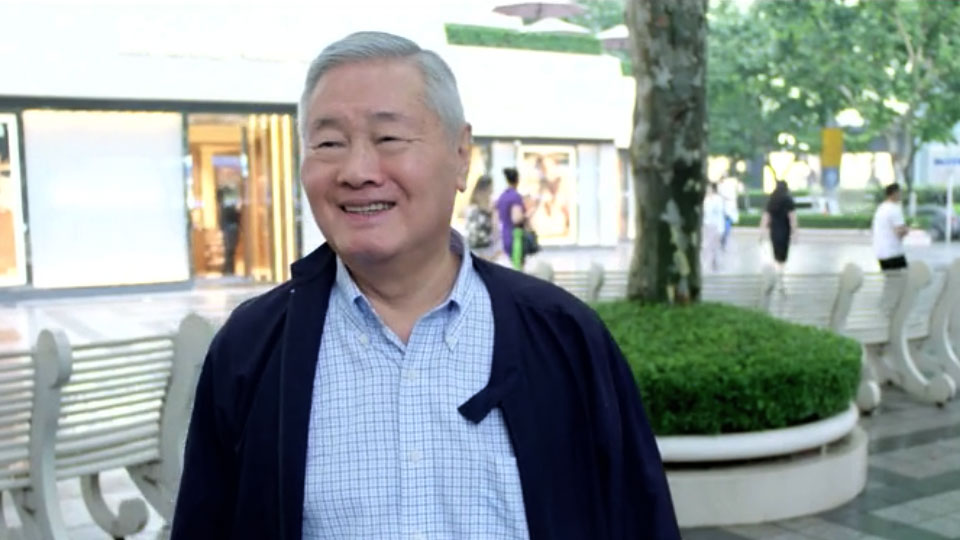

Feng Shan Ho, Chinese Consul in Vienna

Feng Shan Ho was born in poverty in the rural town of Yiyang in 1901 and raised by his mother, an illiterate widow. He was able to improve his situation by excelling at school. He attended Yale-in-China (Yali) College in Changsha in Hunan province, which had been established by Americans at the end of the Qing dynasty, and became fluent in English, German and Spanish.

Feng Shan Ho was born in poverty in the rural town of Yiyang in 1901 and raised by his mother, an illiterate widow. He was able to improve his situation by excelling at school. He attended Yale-in-China (Yali) College in Changsha in Hunan province, which had been established by Americans at the end of the Qing dynasty, and became fluent in English, German and Spanish.

Soon after graduating, in 1927, chaos caused by the Chinese civil war (a period known as the Warlord Era) forced Ho to flee, finding refuge eventually in Shanghai. He had nothing but the clothes on his back and twelve dollars. Through an acquaintance, he was able to find cheap accommodation and work as a tutor for the children of the former governor of Hunan, and later taught English literature at a college in a Shanghai suburb. When the political situation stabilized in 1928, Ho returned to Hunan to work in the provincial foreign office. Not long after, he had the opportunity to take an exam to study abroad. He aced the exam, and went to the University of Munich where he earned a PhD in economics. Several years later, after a stint at the Chinese legation in Ankara, Ho was promoted and sent to the Chinese legation in Vienna, Austria.

Movie Clips

To promote understanding of China, Ho established the Chinese-Austrian Cultural Association, and he gave many talks on Chinese culture and Confucian thought that were popular among Austrians. There was little awareness of the current political situation in China, the Japanese aggression that, in the summer of 1937, was reaching new extremes of brutality. Ho spread the word by giving lectures and publishing a booklet entitled China Defends Herself.

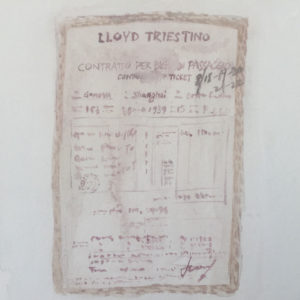

Ho was hosting a meeting of the Chinese-Austrian Cultural Association when he learned that the German army had crossed the Austrian border and would be in Vienna by morning. The Anschluss changed the status of the legations in Vienna, and Ho (whose boss was transferred to Turkey) became Consul General. Witnessing the escalation of violence against the Jews, Ho began working with the American church and other charity organizations to help them, and realized that issuing visas to Shanghai would enable them to escape. In defiance of direct orders from his supervisor the Ambassador to Germany who sought to placate the Nazis, and despite an investigation for corruption, he continued to issue visas to everyone who applied.

It is believed thousands of Jews were able to escape Austria as the result of the visas Ho issued before he was recalled to China in 1940. After the Communist victory in 1949, he followed the Nationalist Government to Taiwan and subsequently served as Taiwan’s ambassador to several countries including Egypt and Mexico. He retired to San Francisco in 1973. In 2001 he was posthumously awarded the title “Righteous among the Nations” by the Israeli organization Yad Vashem.

A Short History of Shanghai

City Above the Sea

Movie Clips

Shanghai, which means “Above the Sea” lies on the Wampu river near the delta where China’s main waterway, the 5,500 kilometre-long Yangtze River, meets the Pacific Ocean. Before the 11th Century, Shanghai’s location was under water. As the waters receded, the fishing village that became Shanghai was on the sea. It became increasingly important as a port for commercial exchange in the 13th century, and a centre for textiles and handicrafts.

Opium Wars / Treaty of Nanking

In the first half of the 19th century the rapidly expanding British Empire was looking for a market for the opium produced in its colony in India and thus massively increased its import of opium into China, with devastating social consequences for the Chinese. When the Qing dynasty attempted to stem the flow, the British, with their mighty navy, declared war. Facing sure defeat, the Chinese signed the Treaty of Nanking granting Britain (and subsequently France, Germany, Russia, Japan and the USA) significant concessions in Shanghai, over which foreign powers had complete control, through a Municipal Council comprised of foreign businessmen. Cultures mixed, while banks and merchants flourished, attracting thousands of migrants from abroad and across China.

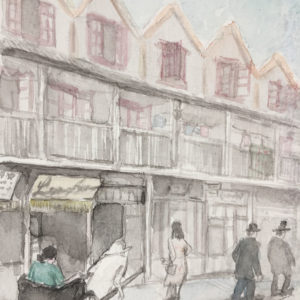

Pearl of the East

Shanghai became known as “Pearl of the East” for its vibrant cultural and night life comprised of theatres, concerts, jazz clubs, casinos, bars and opium dens, and any other indulgence imaginable. But the grandiose banks, hotels, and luxurious Western-style mansions of the foreign concessions stood in stark contrast to the crowded slums that housed most Chinese, who provided the cheap labour that kept the city running. The Communist Party held its first meeting, in Shanghai, in 1921.

Shanghai became known as “Pearl of the East” for its vibrant cultural and night life comprised of theatres, concerts, jazz clubs, casinos, bars and opium dens, and any other indulgence imaginable. But the grandiose banks, hotels, and luxurious Western-style mansions of the foreign concessions stood in stark contrast to the crowded slums that housed most Chinese, who provided the cheap labour that kept the city running. The Communist Party held its first meeting, in Shanghai, in 1921.

The Great War of Resistance and the Battle of Shanghai

In 1931, the Empire of Japan invaded Manchuria and threatened all of China in a wave of expansionism that had begun in the latter half of the 19th century. An exchange of gunfire in 1937 escalated into the Battle of Shanghai and the beginning of total war between the two countries. Despite being relatively ill-equipped, the Chinese resisted with a ferocity that surprised and infuriated the Japanese, who unleashed unprecedented brutality on the civilian population. Tens of thousands of Chinese sought refuge in the International Settlements, which the Japanese were careful to avoid in an aerial campaign that destroyed much of Chinese Shanghai. During three months of fighting, the Japanese suffered 40,000 casualties, the Chinese over 187,000.

World War Two

As war began in Europe, the Japanese continued to occupy Chinese sections of Shanghai, but the International Settlements remained under control of the Municipal Council; it was still an “open city,” with no passport control that might have prevented European Jews from seeking refuge on its shores. Only after Pearl Harbor, in December 1941, and declarations of war between Japan and the Allied powers, did the Japanese occupy the International Settlements. Citizens of Allied countries were rounded up and forced into concentration camps. In 1943, European Jews – who were stateless – were forced into a ghetto in Hongkew, which had been heavily damaged by the bombing campaign in 1937.

As war began in Europe, the Japanese continued to occupy Chinese sections of Shanghai, but the International Settlements remained under control of the Municipal Council; it was still an “open city,” with no passport control that might have prevented European Jews from seeking refuge on its shores. Only after Pearl Harbor, in December 1941, and declarations of war between Japan and the Allied powers, did the Japanese occupy the International Settlements. Citizens of Allied countries were rounded up and forced into concentration camps. In 1943, European Jews – who were stateless – were forced into a ghetto in Hongkew, which had been heavily damaged by the bombing campaign in 1937.

Postwar Period

When the Communists established the People’s Republic of China in 1949, most remaining foreigners left Shanghai. In 1951, Mao expelled, with few exceptions, all remaining foreigners from China. The city remained an industrial centre and the largest contributor of tax revenue to the central government though periods of famine and drought in the country. Shanghai was also an important base of operations for the Cultural Revolution. In 1972, Shanghai hosted the meeting between Premier Zhou EnLai and U.S. President Richard Nixon, resulting in the Shanghai Communiqué that normalized relations and encouraged China to open talks with the rest of the world.

The Dragon’s Head

In 1990, China’s leader Deng Xiaoping said, “If China is a dragon, Shanghai is its head.” Shanghai has since been a key driver of China’s economy, a centre of transportation, commercial activity and international investment. Today Shanghai is once again China’s most open city, both culturally and economically.

A Short History of the Jews in China

Kaifeng 10th – 17th centuries

Movie Clips

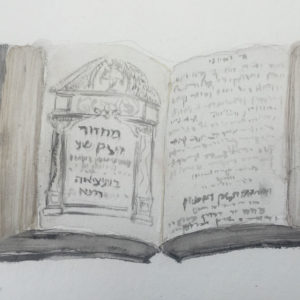

It is believed the earliest groups of Jews began arriving in China, via the Silk Road, in the 8th Century. But it was circa 960 CE that a large group of Jews arrived in the capital of the Northern Song Dynasty and became known as the Kaifeng Jewish Community. They were welcomed with open arms, allowed to keep their own traditions and faith, while enjoying all the same rights as their Chinese neighbours. They built a synagogue at the heart of the city. The Kaifeng Jews prospered, known for their skills in business and the crafts; at its height the community numbered between four and five thousand.

Other communities sprang up in Yangzhou and Ningbo. Records show that when flooding and fires destroyed the synagogue in Kaifeng, these other communities responded by sending new Torahs and books to Kaifeng. A new Torah even arrived with the help of a Muslim from Shanxi province who had acquired it from a dying Jewish acquaintance. Over the centuries, as fewer rabbis and teachers arrived from the outside to teach Hebrew and as the Chinese Jews married outside their faith, the Jewish community in China became assimilated into Chinese Confucian culture, while some converted to Islam. In 1810, the last rabbi in Kaifeng passed away. In 1860, the crumbling synagogue in Kaifeng was destroyed, and the last Kaifeng Jews were reduced to selling holy books and even the tiles from their lost synagogue to Protestant ministers interested in the history of the Chinese Jews.

Encounters with Europeans

Movie Clips

As European explorers and missionaries began reaching China in the late Middle Ages, the presence of Jews in the country was often noted in their reports. The Venetian explorer Marco Polo described the prominence of Jewish traders in Beijing on a visit in the late 13th century. Likewise, the Franciscan John Montecorvino, who became the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Beijing referred to the presence of Jewish traders in that city in the 14th century. Perhaps most famously, in 1605, the Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci encountered a Kaifeng Jew named Ai Tien in Beijing. Ai had entered a church and mistook an image of Mary with the infants Jesus and John the Baptist for one of Rebecca with Jacob and Esau. Ricci sent messengers to the Jewish religious leaders in Kaifeng who, he was surprised to learn, had never heard of Christians.

Mizrahi Jews

In the 19th century, as a result of the Opium War and an upsurge of trade with Britain, Mizrahi Jewish merchants and businessmen from British-controlled cities like Baghdad, Singapore and Bombay, came to China to take advantage of the open trade routes available through Hong Kong and Shanghai. Thriving import-export trade brought great wealth, most notably to the Sassoon, Hardoon and Kadoorie families, among others. These families subsequently supported the development of Jewish culture and community, building synagogues and schools. They also engaged in charity work and public welfare projects. They provided crucial aid to Russian Jewish immigrants and European Jewish refugees as they arrived in China.

In the 19th century, as a result of the Opium War and an upsurge of trade with Britain, Mizrahi Jewish merchants and businessmen from British-controlled cities like Baghdad, Singapore and Bombay, came to China to take advantage of the open trade routes available through Hong Kong and Shanghai. Thriving import-export trade brought great wealth, most notably to the Sassoon, Hardoon and Kadoorie families, among others. These families subsequently supported the development of Jewish culture and community, building synagogues and schools. They also engaged in charity work and public welfare projects. They provided crucial aid to Russian Jewish immigrants and European Jewish refugees as they arrived in China.

Russian (Ashkenazi) Jews

The rising tide of anti-Semitism in Russian and Eastern Europe in the 1880s, and the Russian revolutions of 1905 and 1917, prompted a migration of Russian Jews to China. Initially, they settled in the northern city of Harbin, but following the invasion by Japan, most moved to cities in the south, in particular Shanghai. Initially very poor, with help from Mizrahi Jews, many rose to the middle class and contributed much to the economic and cultural development of the Jewish and Chinese communities.

The rising tide of anti-Semitism in Russian and Eastern Europe in the 1880s, and the Russian revolutions of 1905 and 1917, prompted a migration of Russian Jews to China. Initially, they settled in the northern city of Harbin, but following the invasion by Japan, most moved to cities in the south, in particular Shanghai. Initially very poor, with help from Mizrahi Jews, many rose to the middle class and contributed much to the economic and cultural development of the Jewish and Chinese communities.

Jews in the Communist Party

Over the course of WW2, several Jews, from the US, the UK and Europe, who arrived in China as soldiers or refugees, joined the Chinese Communist Party, and served in various capacities, some as translators, journalists and doctors. By the time the People’s Republic of China was established in 1949, most of the Jews in China had emigrated to Israel or to the West; any remaining Jews (along with all other foreigners) were effectively kicked out by Mao in 1951, but a few of these Jewish Communists stayed, and rose to positions of prominence in the party. These include American Sidney Rittenberg, who served as an interpreter to top Chinese officials, the Polish journalist Israel Epstein, and British activist David Crook. All three were later imprisoned during the Cultural Revolution. Rittenberg was released and rehabilitated in 1977 and returned to the US in 1980. Epstein was released in 1973 with an apology from Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai. He was editor-in-chief of China Today and died in Beijing in 2005.

Over the course of WW2, several Jews, from the US, the UK and Europe, who arrived in China as soldiers or refugees, joined the Chinese Communist Party, and served in various capacities, some as translators, journalists and doctors. By the time the People’s Republic of China was established in 1949, most of the Jews in China had emigrated to Israel or to the West; any remaining Jews (along with all other foreigners) were effectively kicked out by Mao in 1951, but a few of these Jewish Communists stayed, and rose to positions of prominence in the party. These include American Sidney Rittenberg, who served as an interpreter to top Chinese officials, the Polish journalist Israel Epstein, and British activist David Crook. All three were later imprisoned during the Cultural Revolution. Rittenberg was released and rehabilitated in 1977 and returned to the US in 1980. Epstein was released in 1973 with an apology from Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai. He was editor-in-chief of China Today and died in Beijing in 2005.

Watercolors by Yao Xin